Ronny Gunnarsson. Writing a systematic review [in Science Network TV]. Available at: https://science-network.tv/writing-a-systematic-review/. Accessed August 11, 2025.

| Suggested pre-reading | What this web page adds |

|---|---|

| This web page provides an overview over the different types of literature reviews. The page presents features typically found in literature reviews of different types of studies. Finally a detailed step by step guide is provided to help you do a literature review.

This web page will make you understand the different types of literature reviews, commonly used terminology as well as giving you more confidence in how to do one (if possible in collaboration with someone experienced in doing reviews) |

“If, as is sometimes supposed, science consisted in nothing but the laborious accumulation of facts, it would soon come to a standstill, crushed, as it were, under its own weight. … …Two processes are thus at work side by side, the reception of new material and the digestion and assimilation of the old.”

Uttered 1885 by John Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, Physicist and Nobel prize winner

Before you initiate in a project you may want to know what others have done. Is the wheel already invented? Or perhaps, what kind of problems seemed to be related to constructing a wheel? Can I avoid these problems? You start by defining your focus of interest, your topic. Before commencing on doing a literature review you may need to spend some time in defining your topic. This can be compared to the layers of an onion where you have a core focus and layers of related topics around. Another approach is to describe all your interests as different circles that partially overlap. How would you describe the area where most (or all) circles meet?

Table of Contents (with links)

Different types of literature reviews

There are different types of literature reviews such as narrative reviews, scoping reviews and systematic reviews, each with a different level of ambition. The demarcation between different types of reviews is not clear cut and different opinions exist. These types can be described as an hierarchy with four levels (partly adapted from Dijkers , Erwin and Higgins ):

| Level — Type | Description |

|---|---|

| A — Narrative review | Literature is not collected systematically using a specific search algorithm. The amount of data extracted from publications are limited. They can’t be reproduced since a detailed description of the search strategy and information extracted from each publication is not published. |

| B — Evidence mapping / mapping review / scoping review / Scoping study | Evidence mapping, mapping reviews, scoping studies and scoping reviews are more or less different words for the same type of review . The recommended label is “scoping review” or “scoping study” . These reviews aim to create a broad review of an emerging or established field and often to map key concepts in the topic of interest . The search is more systematic than in a narrative review using a defined combination of search terms. However, these search terms may not always be possible to define initially in a review protocol . Findings are briefly summarized and described in tables or graphs, the latter are often labelled evidence maps. Scoping reviews collate evidence irrespective of methodological quality of included publications . Hence, an assessment of methodological quality is usually not done in a scoping review . A scoping review is more descriptive in its nature with a synthesis that is not as thorough as in systematic reviews (below) . |

| C — Systematic review without a meta-analysis | A systematic literature review has a more narrow well defined scope than evidence mapping / scoping reviews enabling a more extensive in depth search of this narrow field . More importantly a systematic review also add an assessment of methodological quality of included publications where some publications of lower quality may influence the active qualitative synthesis of best evidence less . Subsequent recommendations will be based upon this. |

| C — Meta-analysis | A meta-analysis is most often a systematic review that also adds a quantitative synthesis (recalculation) of evidence. It will deliver the highest possible evidence for the right topic were included publications are fairly homogeneous. A meta-analysis is not always suitable and can sometimes be a worse option than a systematic review without a meta-analysis. Furthermore, a meta-analysis is sometimes done on handpicked publications not collected through a systematic search. Hence, most meta-analyses, but not all of them, are also systematic reviews |

| C — Qualitative metasynthesis | Qualitative metasynthesis compares a number of publications where empiric-holistic (qualitative) methods were used to summarize their findings . |

| C — Meta-narrative review (=Mixed studies review = Integrative review) | Meta-narrative reviews aim to do a systematic review of studies using either an empiric-holistic (qualitative), empiric-atomistic (quantitative) or mixed methods approach with an ability to embrace studies with very different design and concepts . These reviews are well structured detailing search strategy and data extraction methods following the RAMESES publication standards for meta-narrative reviews . Since they provide enough information to be reproducible they can be considered to be a type of systematic review. Meta-narrative reviews, sometimes referred to as mixed studies review , are specially suited to describe concepts evolving, perhaps in parallel tracks in separate paradigms. |

| C — Realist syntheses | Realist evaluations answers the question what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how in a broad range of interventions . To compile multiple realist evaluations you do a realist synthesis . This follows the RAMESES publication standards stating that enough information about search strategy and information retrieved should be described so the review can be reproduced. Realist synthesis can be considered as a special case of meta-narrative reviews (see above) focused on evaluating what works. |

| D — Systematic review of systematic reviews (=Umbrella Review ) | If several systematic reviews already exist in your topic what should you do? The easiest option is to do nothing and say we already know enough. However, if previous reviews came up with very different conclusions it means we don’t know enough. If that is the case should you do a review of systematic reviews or just a new systematic review addressing any potential shortcomings of previous reviews. Doing a new systematic review (level C above) would be the best option if you suspect there are new publications since the last review. |

| D — Quantitative meta-synthesis (=meta-meta-analysis) | Doing a systematic review of reviews combining results from several meta-analysis into one new conclusion is labelled meta-meta-analysis or quantitative meta-synthesis . Quantitative meta-synthesis is a special case of systematic review of systematic reviews. |

The table above list four levels (A-D) where B is usually more ambitious than A and C is usually more ambitious than B. However, level D is not necessarily more ambitious or “better” than level C .

Demarcation between different types of reviews

The different types of reviews listed above serve different purposes. One type is not necessarily better than another. There might also be varying opinions on the definitions above and the demarcation between these types is a bit fuzzy. It seems that there is less varying opinions about what constitutes a systematic review and more varying opinions about what constitutes evidence mapping or scoping reviews .

A narrative review or evidence mapping is the minimum type of work you need to do before starting any project. Today an increasing proportion of peer reviewed scientific journals would not accept manuscripts presenting a narrative review or a scoping review. Most peer-reviewed scientific journals would expect a systematic review following PRISMA or RAMESES guidelines. Hence, one important question is if you aim to publish your review in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. In a PhD project you would normally expect a systematic review with or without a meta-analysis.

A confusion exists around “narrative reviews” and “meta-narrative reviews” since both contain the word “narrative”. Narrative reviews are not systematic and not reproducible. Meta-narrative reviews contain a detailed description of the search strategy, data extracted and they can therefore be reproduced. Meta-narrative reviews can therefore be considered to be a kind of systematic review but with a different focus than the traditional systematic reviews.

The rest of this page will only talk about systematic reviews (including meta-analysis) and not about doing a systematic review of systematic reviews or quantitative meta-synthesis.

Meta analysis – is it always better?

A special situation is to sum results of several studies and calculate a new result as in a meta analysis. A meta analysis can be made when you do a review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) or some observational studies (see table below). However, a meta analysis can sometimes (less common) also be done including only a limited number of studies. Hence, most meta analyses are systematic reviews but not all systematic reviews are meta analyses. The main reasons for doing a meta-analysis:

- Pooling data to show a clearer picture of what the evidence says. This is usually illustrated with a forrest plot.

- In the situation where many publications have similar outcome variables (homogeneity in outcome) but very different result. A meta-analysis can explore possible confounding factors to why they come up with different result.

- Pooling data can tell us if we know enough or if more studies are needed.

A systematic literature review with a meta analysis is not always better than a systematic literature review without a meta analysis. A meta analysis is usually the best way forward if most of the retrieved publications has a reasonable homogeneity in choice of outcome variables (effect sizes). However, it is very common that retrieved publications are very heterogeneous and in that case it might be better to do a review without meta-analysis rather than excluding most publications and including a few in a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis has the ability to pool data and provide a new result that the single studies could not. Please have a look at this introduction to meta-analysis (prepared by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, La Trobe University and generously support by Cochrane Australia. Written by Jack Nunn and Sophie Hill.):

Grey literature

“White literature” is publications published by commercial publishers whose main task is to publish. Scientific white literature is often peer-reviewed and (unless it is a predatory journal) a fair proportion of submitted manuscripts fall short and are rejected. This process is supposed to enhance the methodological quality of scientific publication. Grey literature is published in a context where the main task is not to publish and it is often not peer-reviewed. However, white literature can sometimes be of poor quality and not very useful while grey literature can sometimes be very relevant to your review. Hence, the appreciation of grey literature is increasing .

There is no given rule as to the use of grey literature in a systematic literature review. In general grey literature may have lower methodological quality compared to white literature. Hence, grey literature tends to be sorted out in systematic literature reviews where a methodological assessment is done. However, grey literature is often incorporated in scoping reviews where a thorough methodological assessment is rarely done.

Heads and tails

A review of what previous researchers have done should preferably be made systematically and presented in a way that it can be reproduced by others. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is a good example of a systematic approach. A systematic literature review builds upon previous publications. This situation can be described as a coin with two sides (“heads or tails”). One side of the coin are advice given to authors of a single original article to ensure highest possible quality (“heads”). The other side of the coin, used in systematic reviews, are different ways to evaluate previously published articles (“tails”). Both sides of the coin (“heads and tails”) contains similar opinions concerning good quality. The tables below elucidates the two different sides of the coin.

Randomized controlled trials

| ⇐ “HEADS” ⇒ | ⇐ “TAILS” ⇒ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups compared | Guide to write original article | Aim for meta-analysis | Guide to write a systematic review* | Examples |

| Yes | CONSORT | Yes |

Previously different scales and scoring were used for assessment of methodological quality of RCTs. Example of scoring systems used were Jadad , the Delphi list , Maastricht-Amsterdam List (MAL) , PEDRO and CASP. However, many more scales exist . These scorings were used to separate studies of high or low quality by introducing a cut off in the scale. This may then be used to establish levels of evidence for a specific topic. However, for randomized controlled trials we now recommend that you follow the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias graphically without directly calculating a score . For meta-analysis please read more about doing a meta-analysis on the Cochrane collaboration website. For randomized controlled trials involving animals please look at ARRIVE , SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies or CAMARADES . |

Comparison of Aspirin, Warfarin, and New Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention . (example of a meta-analysis) |

| Yes | CONSORT | No |

Treatments in whiplash-associated disorders . (Example of establishing best-evidence synthesis). Dendritic cells prolong the survival of renal allografts . (Example of review of lab based research) |

|

* Follow PRISMA or CAMARADES where it applies and also guidelines found below (where they apply).

Observational case-control / cohort studies

| ⇐ “HEADS” ⇒ | ⇐ “TAILS” ⇒ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups compared | Guide to write original article | Aim for meta-analysis | Guide to write a systematic review* | Examples |

| Yes | STROBE | Yes | The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) or CASP can often be used as a basis. Quite often you may need to modify or add a few elements tailored to your topic. Use MOOSE if you pool data and make a meta-analysis. | Growth factor and coronary heart disease

Risk Factors for Conversion of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy . |

| Yes | STROBE | No | The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) or CASP can often be used as a basis. Quite often you may need to modify or add a few elements tailored to your topic. | Risk factors for conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy . (example of how to define methodological quality assessment – Table 3 – and the subsequent outcome – Figure 2) |

* Follow PRISMA or CAMARADES where it applies and also guidelines found below (where they apply).

Other observational studies

| ⇐ “HEADS” ⇒ | ⇐ “TAILS” ⇒ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups compared | Guide to write original article | Aim for meta-analysis | Guide to write a systematic review* | Examples |

| Yes | STROBE | Yes | There are a few scales that sometimes may fit such as QUACS or CASP. However, you often need to construct a scale relevant for the topic you study. Look at examples to the right first. Avoid using a quality sum score and instead present quality as a figure (The reference is an example for RCTs but can be adapted to other types of studies). | Depression in chronic kidney disease . (example of presenting risk of bias as a figure – figure 2) |

| Yes | STROBE | No |

There are a few scales that sometimes may fit such as QUACS , CASP or MMAT . However, you often need to construct a scale relevant for the topic you study. Look at examples to the right first. Avoid using a quality sum score and instead present quality as a figure (The reference is an example for RCTs but can be adapted to other types of studies). For anatomical studies consider the AQUA tool . |

Patency after Balloon Angioplasty in Hemodialysis Fistulas. (example of quality assessment – Table 2)

Postoperative Adverse Events & the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist (example of quality assessment – Figure 2-3) Orthorexia nervosa . (example of an integrative review – focusing on how publications relate to different epistemological paradigms) Staff Acceptance of Tele-ICU Coverage . (example of an integrative review – including studies with a qualitative approach). Staff Women and HIV (example of an integrative review) |

* Follow PRISMA or CAMARADES where it applies and also guidelines found below (where they apply).

Evaluation of diagnostic tests

| ⇐ “HEADS” ⇒ | ⇐ “TAILS” ⇒ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups compared | Guide to write original article | Aim for meta-analysis | Guide to write a systematic review* | Examples |

| No | STARD | Yes | QUADAS or a modification of it . An alternative is CASP Diagnostic checklist. | (Coming) |

| No | STARD | No | QUADAS or a modification of it . An alternative is CASP Diagnostic checklist | (Coming) |

* Follow PRISMA or CAMARADES where it applies and also guidelines found below (where they apply).

PICO

One goal of Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) is to collect scientific evidence for common clinical questions. The best way to do this is to ask the right questions. Sackett first suggested a framework for how to come up with well defined and answerable questions . The framework says each question should be structured in the PICO format; Patient or Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome/s. The following video describes (in a funny way) evidence based medicine and PICO:

The PICO format is perfect for clinical questions around choice of therapy (where no therapy might be one of available choices). However, the PICO framework is less suitable for questions other than around choice of therapy .

In conclusion, strive to use the PICO format if your question is about choice of therapy. For other questions use suitable parts of the PICO framework. There might also be questions where all parts of the PICO framework, at least as conventionally described, are unsuitable. Hence, be aware of the PICO framework but only refer to it if it helps in your situation. Don’t try to squeeze everything into the PICO framework.

How to do a systematic review

Write a preliminary scope

Describe the preliminary scope of your review and put it down in writing. Drawing overlapping circles where one circle is one topic may be a useful tool. Try to describe your scope as a union between two or more circles. Use the PICO framework if relevant. Once you have played around with circles a while try to write down a preliminary topic for the review with preliminary inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Is the wheel already invented?

- Do a search in relevant databases for published systematic reviews relevant to your scope. Carefully document what you find.

- Go to PROSPERO – An international prospective register of systematic reviews for human research (or CAMARADES for animal research) and search for ongoing, not yet published, reviews covering your scope.

- If you found any published or ongoing reviews that seems identical to your scope then you may have to change scope. If so revise the scope of your review and document in writing the revised scope of your review as a new topic with new inclusion and exclusion criteria.

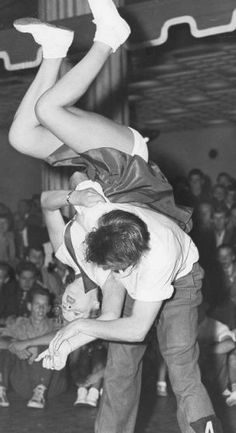

Dance

Test different combinations of search terms to find a relevant combination resulting in hits relevant to your scope. A good combination will yield approximately 50% of hits being relevant (it is difficult to find search term giving a higher yield of relevant publications).

You also have to consider the number of hits from your search and your available resources. One or two persons doing a review may embrace a thousand titles reading approximately 500 abstracts, retrieve up to 100 full text publications and after reviewing them include 10-70 full text publications in the assessment. These numbers can be increased if you have more resources (more staff) available. You need to rethink if you get much more hits than you can manage with available resources. If that is the case revise the scope of your review again and test a new search strategy. This is like a dance between testing search terms and fine tuning the scope of the review.

Finalise your review protocol

- Carefully document the final scope of your review with a final set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria are characteristics / criteria that a publication must have to be included. Please note that publications must fulfill ALL inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria are factors, other than inclusion criteria, that makes the study ineligible to be included. It is enough if a publication fulfills one exclusion criteria to make it ineligible. Hence, please note that the exclusion criteria in a literature review is not simply the mirror of the inclusion criteria. Please have a look at “Eligibility criteria” (in the Methods section) of this example of a review about the link between confusion and urinary tract infections (follow the DOI-link to see the example).

- Define a final relevant set of search terms. Carefully document the final version of set of search terms.

- Describe what information you plan to extract from each publication and how you plan to present it. It is common to write that a meta-analysis will be done if retrieved publications are homogenous in respect of type of observations (type of patients) and how observations (patients) are observed / measured.

- Describe how methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment of each single included publication will be done and how it will be taken into account when you make your final conclusions. It was previously common for randomized controlled trials to score them according to an accepted scoring system. However, it is now more common to present this as a figure rather than calculating a score for each publication . Should studies with overall poor quality be ignored partly or completely? Please write this down and ensure it is expressed in your final publication.

Please note that “level of evidence” / “hierarchy of evidence” is used to summarize the evidence for an intervention / practice from multiple publications. “Level of evidence” / “hierarchy of evidence” is NOT suitable to assess single publications evaluating an intervention.

The methodological quality of a publications evaluating an intervention in a randomized controlled trial needs to be evaluated in a different way than publications using other techniques than randomized controlled trials. Some advice might be found from examples in the tables above but you may have to construct your own adaptation of how to assess the methodological quality of single publications. - The above steps should give you enough information to be able to write down a review protocol detailing how you plan to execute your review.

Register your review

Register your systematic review in a register of systematic reviews. This is mandatory for reviews of randomized controlled trials and recommended for all other reviews. It is very important to register your review before you do the final search (because registration may be denied if you have come too far in the process).

To register your review go to PROSPERO – An international prospective register of systematic reviews for human research (or CAMARADES for animal studies). Ensure you state that the final search for literature is not yet done. Examples of registrations in PROSPERO of systematic reviews that are not meta analyses:

- Depression in non-professional caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review of predictors of psychological distress.

- Parents of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review of psychological distress and adjustment.

Do the final search and sort publications

- Do the search using your final set of search terms. You must do the search in at least two publication databases and the set of search terms will be very similar (though not identical) in each database. Carefully document the hits in each separate database ignoring that many publications are duplicates. (All this needs to be written in the PRISMA flow chart).

- Import the hits from each database into a reference managing software (EndNote or similar) and let the reference managing software merge the hits to one single list of publications, eliminating all duplicates. Carefully document the number after removing duplicates.

- Scan through all titles and read selected abstracts. Decide which titles seems relevant. Carefully document this step.

- Read abstract for all articles where the title seems relevant. Carefully document why some articles were not chosen.

- Retrieve and read the full text articles where the abstract seemed relevant. When you read the full text you will find a few articles that are actually not relevant for your review. Carefully document why some full text articles are omitted.

- Study reference lists within the remaining set of relevant articles to find a few more articles. Include them in the final list of relevant articles. Carefully document this step

Ideally step 3-6 should be done by two separate persons comparing their final lists and discuss differences to jointly come up with a final list of publications to include.

Extract information

When reading publications in the final list of included publications ensure you extract a) relevant data previously decided upon and, b) assess methodological quality of each publication. Ideally both of these should be done by two separate persons comparing their outcome and discussing differences to come up with a joint final data extraction sheet.

Make strategic decisions

Are data homogeneous enough to allow a meta-analysis? It is usually better to refrain from doing a meta-analysis if the included publications are heterogeneous. If you can’t do a meta-analysis can data from each publication be recalculated to be more similar. An example of the latter might be that a set of randomized controlled trials use different sets of patients or a different outcome measure and can therefore not be used for a meta-analysis. However, it might be a good idea to ensure that cohen’s d or some other effect size can be presented for each publication. The original publications may provide this but if they don’t consider if it can be calculated from results provided in the original publication.

Effect size or meta-analysis is of course irrelevant of your review includes many studies using other paradigms than the empiric-atomistic paradigm (see web page about philosophy of science).

Writing up your systematic literature review

Systematic reviews can be a shortcut to grasp the outcome of many studies. However, remember that the outcome of a systematic review depends on a number of decisions made during the process .

Write the article following guidelines from PRISMA, CAMARADES or other relevant guidelines. You will find good advice on how to write a systematic review in Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews in health care. (Start by looking at Box 1.11 on page 78). You may also find the explanation of the PRISMA checklist useful . Also see advice below about how to write this up.

Content of your manuscript and author instructions

Overall layout

A manuscript for submission should not have a nice graphical layout. This is something the journal adds on after the manuscript is accepted. They have their own methods to address this. Any graphical stuff added before just makes their job more difficult. This means that most journals don’t want you to put tables into the text. Some journals want you to put a placeholder (a kind of notation) describing where you would prefer a table. They still want you to have a table either as a separate page later in the manuscript or, as a completely separate file. The desired layout of your manuscript is for most journals:

- Title page

- Abstract / Summary

- Introduction / Background

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Acknowledgements

- References / Bibliography

- Tables

- Figures

All scientific journals have author instructions. Study them carefully and follow them. Some journals may want you to submit without a title page. Some journals want the tables and figures as the last part of the manuscript. Other journals want you to upload tables and figures as separate files. Some journals may want the acknowledgement in another place. All text should be written with 1.5 or 2 in line spacing. Most journals prefer a font size of 12. The maximum allowed length of a manuscript varies depending on journal. Item 4-8 above should be headings in your manuscript. Item 3 (Introduction) is also a heading in some journals while in others the background text starts directly without a heading.

Check in author instructions how long (how many words) your manuscript can be. A few journals have no word limit. However, most journals have and for a literature review it would usually be somewhere between 2,500-4,000 words. The shorter the more likely it is read. It is difficult and very time consuming to shorten a manuscript expressing yourself more succinct. However, if successful the reader will experience a well digested interesting text that reads more easily. For every sentence you need to ask yourself – is this sentence really necessary? Can I refer to the original publication instead of describing all details? Once you have gone through all sentences you need to start over and ask for every word – is this word really necessary? Have a look at some of the examples given in the table above.

Title page

Contains the title, list all authors and states all author’s affiliation. I also states who is corresponding author. Identify the manuscript as a systematic review (and meta-analysis if relevant) in the title. The title page is a separate page. Some journals prefer it to be the first page of the document. Other journals want it as a separate file.

Abstract / Summary

Look in the PRISMA checklist and the author instructions for the journal to figure out what subheadings you need in the abstract. The abstract is usually also a separate page coming after the title page but before the introduction. Hence, the introduction starts on a new page.

Paragraphs in Introduction-Background

Your introduction-background should consist of a few paragraphs that works like a red cord. Each paragraph prepares the way for the next paragraph:

- Begin with describing the topic and why it is an important topic. You may want to mention prevalence or costs associated with this topic. You are not supposed to write a new textbook here so this paragraph must not be too long.

- The rationale for a project is always to solve a problem. In this paragraph describe the unresolved problem associated with the topic. The problem may be (a few examples):

-We may have different treatment options for disease X. It is unclear what the effect of these treatment options are.

-It is unclear how patients with a higher risk should be identified.

-The correlation between different risk factors and an unwanted outcome is unclear.

(1 and 2 may be combined into one paragraph) - Once you have defined the topic and the associated problem then you need to state what others have done to solve the problem. In the case of a systematic literature review you need to describe all previously published literature reviews, including reviews that are not systematic and that did not follow the PRISMA guidelines. Sometimes you (and your advisors) may find that to your knowledge there are no previously published literature reviews. If that is the case state state this rather than just not addressing previous reviews. (If there are no reviews then this paragraph will only be one sentence and if that is the case I recommend that you combine this sentence with 1+2 above).

- In the previous paragraphs you have described the topic, the remaining problem and previous systematic reviews to shed light on the problem. If previous literature reviews sheed enough light on the problem (solved it completely) then there would not be a need for a new systematic literature review. Thus, you need to describe, in light of previous published reviews, why a new review is needed. If there are no previous reviews then you still need to state why we need a literature review. This is the rationale for your project.

- State the aim. An example might be “Accordingly, we conducted a meta-analysis combining publically available data with the aim of …” or “We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of… ” or “The aim of this review was to systematically examine studies which have… “. (This aim can often be combined with 4 above into one paragraph).

Paragraphs in Methods

Please read the checklist in PRISMA guidelines under the section “Methods”. This gives good advice on the paragraphs you expect to find here. When you describe the search strategy you have the choice of describing in text or refer to a table describing your key words used.

Paragraphs in Results

Please read the checklist in PRISMA guidelines under the section “Results”. This gives good advice on the paragraphs you expect to find here. When you refer to “Study selection” you should refer to the PRISMA flow chart as a figure. You can download this figure as a Word file from the PRISMA homepage so you don’t have to make that figure yourself, just change text and figures.

Remember that the text in the results section should not simply repeat facts from tables. The text should guide the reader and point out the main trends referring to tables and references where relevant. Repeating details from each publication in the text makes it difficult to read and grasp. Hence, actual findings should be summarised in sub-themes or topics rather than describing every publication (the latter should be done in one or several tables where the reader can look up details). If your review focus on an intervention this would be the place to state the level of evidence for each finding. Please also note the advice on significant figures.

Paragraphs in Discussions

- Begin with a short summary of your main findings (results). Don’t describe all findings here, just the most important ones. This summary should be very short (1-3 sentences).

- In the following sections summarize your most important findings, without repeating details from the results, and discuss its relevance for different readers. Why do some previous publications end up in opposite conclusions? What do we really know when the existing literature is compiled? What are the consequences for doctors, policy makers, etc.

- Describe strength and weaknesses with this review.

- What is your final conclusions around your findings. Also try to clarify for the reader what your review adds compared to previous existing reviews. What was your unique contribution. Finally, try to identify the need for any future studies that you think should be done?

The most common pitfall in writing a systematic literature review is to simply repeat the results in the discussion without any deeper conclusions. A good discussion should not repeat results but rather explain peculiar results and provide possible explanations to why some findings in the literature are contradicting. It should be enjoyable to read and end in understandable take home messages. Writing a good discussion is probably the most challenging part of writing a good systematic literature review and this is often the part that ultimately decides if it is going to be published and read.

Tables

The decision to put information in a table or purely in the text (usually under the heading Results) depends on the amount of information. Small amounts of information should be described solely in text. The more information you can arrange into a table the better. However, there is an upper limit where tables tends to be too big and difficult to grasp. Always carefully consider if all information is necessary. The problem of information overload tends to be more common than the problem of providing too little information (although the latter exists as well). Also consider the number of tables you want to have. Few journals would accept more than five tables. In most manuscripts you can often do well with 1-3 tables. I recommend that you have a look at tables in the examples given previously (in the large table). A few things to consider:

- Start each table on a new page. On a Windows computer you create a page break with Ctrl+Enter.

- Tables should normally only have a few horizontal lines and no vertical lines. Cells should not be filled with colors.

- Every table should have a numbering and a title following the numbering (see examples given above).

- Most tables need some kind of footnotes to clarify some details.

Figures

The first figure is usually the PRISMA flow chart. You can download this figure as a Word file from the PRISMA homepage so you don’t have to make that figure yourself. Just change text and figures and insert this page in your Word manuscript. Ensure that all figures given in the flowchart sums up. This is usually your only figure (if you are not doing a meta-analysis). Each figure should start on a new page and figures should all be placed after tables.

Acknowledgements

Thank staff and participants for their contribution. Do not thank authors (they get their fame by being authors). When it comes to staff be specific on what they did that you want to thank them for. Describe any funding and potential conflict of interests.

References / Bibliography

There are two main systems for presenting references; Harvard and Vancouver. Each journal tends to have its own variation of any of these. This means that the reference list and the annotations in the text are specific to a journal. Follow author instructions regarding reference style carefully. A good software for managing references, such as EndNote, will save you a lot of time. The importance of these software cannot be overestimated.

Examples you can follow when writing up

- (Coming)

Finding a journal to submit your manuscript to

The best way to make your findings easily accessible is to submit them to a scientific journal. This journal has routines to ensure your publication is indexed in the right publication and citation databases. There are different pathways to find the best journal for submission:

- First write your manuscript as you want (following guidelines given further down on this page). Once you are finished have a look at your own reference list in your manuscript. You cite journals in your reference list because they have published other studies relevant to your study. Hence, they are likely to be interested in your research. Have a look at the journals found in your own reference list. Which journals do you cite most often? This will give you a shortlist of 3-5 possible journals. Also check their impact factor? Decide which one you want to try first. Make minor adjustments to your manuscript to tailor it to this journal. If it gets rejected by the first then you already have an idea of where to send it next.

- Find the journals in your topic with the highest impact factor before your manuscript is written and tailor your writing according to these author instructions.

- Ask Jane.

Before finally deciding check that the journal you aim to submit to…

- …is indexed in at least one of the main citation databases such as Thomson Reuter’s Web of Science or Elsevier’s Scopus (follow these links and see if the journal you plan to submit to is indexed there).

- …is not a journal being on a predatory journal black list such as the Cabells list.

- …and if possible has an open access policy not requiring a subscription to read any of their content (full open access).

More practical tips

The webpage Writing a scientific publication has valuable practical tips. I would specially point out the sections:

- A few tips when using Word or similar software

- Academic writing

- Using a translator or language editor

- After submission – Rejection

- After submission – Checking a proof and answering questions if accepted

- Plagiarism – a gateway to hell?

Software

There are different software that can help you doing a systematic review. The main focus for most of them are to facilitate a meta-analysis. Some of them are free while others cost money. A few examples are:

- Rewman Web by the Cochrane community (free)

- Rewman 5 by the Cochrane community (free). This is a stand alone software to be installed on a local computer. It is not updated and the intention is that Rewman Web will replace Rewman 5.

- MetaEasy Excel add-in (free)

- Meta-Essentials: Excel workbooks for meta-analysis (requires Microsoft Excel but is otherwise free).

- The metafor Package: A Meta-Analysis Package for R (free but require the statistical software R that is also free).

- MetaDigitise is an R package that provides functions for doing a meta-analysis (free but require the statistical software R that is also free).

- Rayyan QCRI is a free software to help systematic review authors that also has a mobile app. This software is developed at Qatar Computing Research Institute (Data Analytics).

- EPPI-Reviewer (available for a subscription fee).

- Joanna Briggs Institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information (JBI SUMARI). (available for a subscription fee).

- Polyglot search – a website developed by Bonds University in Australia that creates or translates your search terms to several literature databases.

There are many more software available. A good place to start looking for them is the systematic review toolbox.

Useful links

- Read more on the homepage for PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). The PRISMA Statement consists of a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram. Have a look at the checklist and flow diagram before you start. Please also have a look at the examples given above.

- AMSTAR describing good quality of a systematic literature review.

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine – Toronto

- Appraisal Tools at the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)

- Software for Publication Bias by Michael Borenstein

References

Ronny Gunnarsson. Writing a systematic review [in Science Network TV]. Available at: https://science-network.tv/writing-a-systematic-review/. Accessed August 11, 2025.