Ronny Gunnarsson. Philosophy of Science [in Science Network TV]. Available at: https://science-network.tv/philosophy-of-science/. Accessed July 2, 2025.

| Suggested pre-reading | What this web page adds |

|---|---|

| None | This web page describes the most important cornerstones of Western philosophy of science. It is not complete and, if necessary, will be supplemented and revised. Philosophy of science is based on the parts of philosophy that asks questions about the nature of scientific knowledge. How do we know what scientific knowledge is and how does it differ from any kind of knowledge? Which pathways are acceptable and trustworthy when you create new scientific knowledge? This web page begins by describing the development of scientific thinking until post positivism after which a very brief overview of philosophy is given. The web page continues with a brief description of how human science has developed. Many names of people are mentioned (and more names should perhaps be mentioned) but there’s no need to learn all the names by heart. Towards the end, a proposal for what may be worth remembering is given. |

Table of Contents (with links)

Philosophy of science in the ancient world

Different cultures developed extensive knowledge in astronomy, mathematics and medicine during thousands of years. This knowledge described practical steps of how to accomplish something. The purpose of this knowledge was generally to solve practical or religious problems. There were not much of theories around production of new knowledge. In ancient times (around 700BC – 400AC) things start to happen around the Mediterranean.

Leaving the superstitious thinking

Philosophy of science in the western part of the world is considered to have begun with various natural philosophers in Greece in 600 BC. They began to gradually distance themselves from magical religious and superstitious thinking. The first known Western philosophers before Socrates was Thales (625-545 f. Kr.) He lived in the city of Miletus on the western coast of Asia Minor, which is considered one of the first thinkers of philosophy of science. Other famous thinkers before Sokrates was Parmenides of Elea and Heraclitus. They came up with theories and subjected them to critical scrutiny and discussion. That was when science as we know it began.

From the middle of 500 BC to mid 400BC the Pythagorean school appeared in southern Italy. After moving to the city of Croton in southern Italy Pythagoras (570-497 BC) founded this philosophical movement. It was a scientific (and partly also religious) school with mathematics as a main focus. They introduced the theoretical proof, that is, from some initial assumptions and reasoning arriving at new conclusions.

Socrates (470-399 BC) appeared as a debater in Athens around 400 BC. At that time it was common that teachers taught students practical knowledge in such a way that students passively received information that the teacher imparted. Sokrates had a different style. He asked questions in such a way that the listeners in the process of answering the questions learned how to make new discoveries. Socrates debated extensively on many different subjects, including the philosophy of acquire new knowledge. He questioned conventional manners, condition and beliefs so successfully that he 399 BC was executed. His disciples were scattered after the death of Socrates.

Rationality versus empiricism

One of Socrates students was Plato (427-347 BC) who were around Socrates for approximately seven years before the execution. After the death of Socrates Plato made a field trip to the Pythagorean school in southern Italy. Their thoughts on the theoretical evidence made a great impression on Plato which then emphasizes rationalism, an approach that considers logical theoretical thinking superior to experience to reach true knowledge. Plato argued that rationalism was the only way to achieve true knowledge. After returning from southern Italy, Plato creates a mathematical-philosophical school called Academia just outside Athens .

Aristotle (384-322 BC), was a student and later a member of Plato’s Akademia for over 20 years. After Plato’s death in 347 BC Aristotle left Athens and worked partly as tutor to King Philip II’s son Alexander (later known as Alexander the Great). Aristotle believed, in contrast to Plato, that science is primarily a study of the realities. Although Aristotle does not entirely rejected rationalism he preferred empiricism, that is, the idea that all true knowledge is based on observations of phenomena that we can observe. Aristotle held empiricism as more important than rationalism. He stated that it is difficult to acquire knowledge about a phenomenon if we can not observe it.

Atomism versus holism

There is another type of diversity besides the split between rationalism and empiricism. Can everything be understood if one can adequately describe the smallest components of it? Or… … is the phenomenon of interest something else than just the sum of its parts?

Some philosophers, often labelled atomists, argued that all we see are only effects of events among the smallest particles, atoms. An early known atomist was Demokritos (460-370 BC). He claimed that the only thing that exists are atoms and the void. Everything that happens can be traced down to the events among the smallest particles, atoms. This is called reductionism or atomistic approach. The atomistic approach characterized the Knidian medical school in ancient Greece that focused on well-defined separate diagnoses that each had its own special treatment. Positivism is a philosophy that later will evolve from the atomistic approach (see below). Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902 AC) is usually mentioned as a key figure in modern medicine which was heavily influenced by atomism and positivism. Instead of Demokritos atoms, he explained everything using cellular pathology. All diseases could be explained if one understood the events at the cellular level.

Hippocrates (460-370 BC) are as far as we know the first doctor who dismissed superstitious explanations or divine punishment as an explanation for disease. The Hippocratic school had its focus on treatment and prognosis rather than putting distinct diagnoses. The treatments were more passive and focused on the self-healing ability. Since none knew hardly anything about how the body really worked at that time (and thus had limited opportunities to provide medical treatment) Hippocrates approach was more successful than the Knidian school. In the Hippocratic medical school the importance was more on the big picture. They treated sick patients, not diseases. In an explicit holistic approach (holism = undivided, whole) the phenomenon, such as disease, cannot be understood by carefully enough describe the individual small parts. The holistic approach is the basis for the later emerging human science (see below).

Science has for centuries oscillated between being dominated by atomistic or holistic approach. The twentieth century, with traditional medical science is heavily influenced by atomism, positivism and the Knidian medical school.

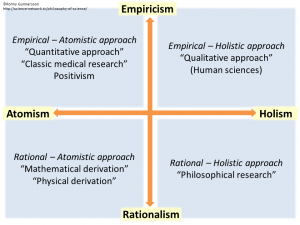

The epistemological world map – different paradigms

It can be helpful to take a quick look at the principally different ways new knowledge can be created before we walk further on the timeline. Epistemology is a major branch of philosophy, which, among other things, is about how we develop new knowledge. As mentioned above, we end up in the following two opposites:

empiricism ↔ rationalism

atomism ↔ holism

Empiricism says that we can only reach new knowledge by observing reality and draw conclusions from these observations. This is called induction. Rationalism says that we best reach new knowledge by starting with known logical assumptions or truths and by logical reasoning discover new truths, something called deduction. A rationalist makes statements about how the world works without study reality.

An atomist says that we can get the whole truth just by studying small well defined parts of reality. It is argued that more general truths can be drawn by summing truths from different defined parts of reality. An atomist considers that the whole phenomenon can be well described just by summing up what we know about the parts. In holism it is stated that the phenomenon is more than the sum of its parts, and most new truths are acquired by the study of small well-defined parts of reality.

We can talk about paradigms in both epistemology (explained further down) and in a particular subject, topic or discipline. Paradigms are the glasses through which you view the world. It tells you what is right or wrong. Atomism-holism and rationalism-empiricism are two opposites creating four different quadrants of the epistemological world map (see Figure). These four quadrants are four different epistemological paradigms stating the correct procedure to create new knowledge. When scientific thinking continues to evolve over the centuries, it is often tension and struggle between these four different paradigms. These quadrants can also be considered as four different continents on the scientific world view. The climate is quite different on these continents. What is considered high scientific quality on one continent might be considered flawed on another.

Scientific progress during the middle ages

Scientists rarely did any experiments to support or falsify their hypotheses during the Middle Ages (from the fall of the Roman Empire around 500AC up to around 1500AC) . Instead they asked how the great ancient thinkers would have solved the problem. The teachings of Aristotle and Plato were preserved and how their ideas could be applied in the present time. Aristotle’s explanation of how the world was made up of the four elements of earth, water, air and fire as well as a fifth unchangeable, heavenly element making up celestial bodies. The celestial bodies floated in various spheres around the earth, as Aristotle assumed to be round. There was a problem getting the planets observed movements to correspond with the theoretical spheres around earth. The theories were therefore expanded with multiple spheres in a complicated pattern to try and make theories fit observations.

The Catholic Church had adopted Aristotle’s teachings and defended them vigorously. Science survived in various monasteries where the idea that ancient scholars had the answers led to a large authoritarianism which inhibited further development of scientific thinking.

During the 1200th century universities grew around Europe from monastic centers of learning. The universities in the Middle Ages were mostly focused on producing administrators, clergy and lawyers to governments and churches. Today’s clear link between universities and scientific development did not exists during the Middle Ages and is something that was added much later.

The scientific revolution

Science involves a systematic and methodical development of knowledge. In the ancient world and during the middle ages contemporary scholars rarely performed experiments to verify or falsify their hypotheses. Hence, philosophy was in reality the only existing branch of science in the ancient world and during the middle ages. No major revolutions in scientific thinking occurred during the middle ages. The scientific revolution is a period which most historians considered to start with Galileo and ending with Newton. During this time it became more common to compare theories with results of experiments and observations of reality. This is called the scientific revolution. With the scientific revolution sciences such as mathematics and astronomy becomes more prominent. As a consequence fundamental changes in the perception of astronomy, physics and biology takes place and the entire worldview is fundamentally changed. Universities and other institutions supporting research change their approach to research.

Astronomy, the new physics and the changing world view

An initially trivial problem would later turn out to be a turning point for the scientific stagnation that prevailed during the Middle Ages. The Julian calendar that Julius Caesar introduced from Egypt led to a gradual shift in the seasons. The equinox, originally on 21 March, had in 1541 moved to 11 March. This happened because the year in the Julian calendar was 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than the time it takes for the Earth to complete one circle around the sun. The Polish-born scientist Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) spent many years studying astronomy, mathematics and medicine. During 1505 he began studying the geocentric model where the sun, the planets and the stars are believed to revolve around the earth. Copernicus established that the planets, including the earth revolved around the sun. Although Copernicus was not the first to describe a helicocentric model, he did it in a systematic way presenting all scientific observations supporting the hypothesis that the planets revolved around the sun.

In 1541 the Pope Sixtus IV asked Copernicus to find out the cause of the fault with the Julian calendar. Copernicus had reliable information from his observations of planets and knew that the solution was to change world view to the helicocentric model where the earth is orbiting the sun. Copernicus realized that the answer could be dangerous as it was contrary to the opinion held by the Catholic Church at that time. He therefore declined the assignment. Copernicus probably planned to let his discoveries go to the grave with him. Through persuasion of the professor of mathematics in Wittenberg Joachim Rheticus, Copernicus finally wrote the book De revolutionibus orbium caelestium Libri VI, where he provides detailed descriptions of his findings and conclusions. The book was published after Copernicus’s death in 1543 and was initially not widely distributed, probably due to opposition from the Catholic Church, the fact that the book was difficult to read and that the author was already dead. However, after some time the importance of Copernicus discoveries were gradually recognized. Some historians put 1543 as the starting date of the scientific revolution.

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), born in Germany was already in his childhood interested in astronomy and astrology. While studying astronomy, he was in the 1590’s convinced that Copernicus helicocentric worldview was correct and that the geocentric worldview constructed by Aristotle and Ptolemy was wrong. Kepler published his first astronomical work Kosmos Mysteries (Mystery cosmographicum) in 1596 where he publicly defended the helicocentric worldview and also discusses planetary orbits around the sun. In 1604 he publishes a book on optical principles. The book was later regarded as the foundation of modern optics. Kepler worked with Tycho Brahe and through his precise observations of the planet Mars, he could construct two laws of planetary motion. The first that the planets move in an elliptical orbit with the sun at one focus of the ellipse. The second law that planetary speed in its path is inversely proportional to the distance to the sun. Kepler published these findings 1609 in the book The new astronomy (Astronomia nova). In 1621 he publishes an expanded second edition of the book Cosmos mysteries where he explains his findings further, and also fix up some previous inaccuracies.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) shared Copernicus and Kepler’s hesitation towards the prevailing geocentric worldview constructed by Aristotle and Ptolemy. Galileo became aware of Copernicus’s works around the same time as Kepler around 1590. In 1609 a Dutch optician discovered that convex and concave glasses could combined to make a telescope. The original use was to spy on enemy troop movements but Galileo directed the newly invented telescope to the sky. Galileo could increase the magnification further after some experimentation. He saw that there were many more stars than you could see with the naked eye and he also saw the rings of Saturn and discovered four moons around Jupiter. Galileo became convinced that Copernicus helicocentric worldview was correct. Galileo discussed his findings with Kepler who reassured him that he was on the right track. When Kepler first heard about Galileo’s discoveries, he began to experiment more in optics and found that two convex lenses could build telescopes with higher magnification than Galileo had with his telescope. Kepler published in 1611 a description of his telescope in the book Dioptrice. Galileo published in 1632 the book Dialogue on the Two World Systems where he clearly explained that the geocentric worldview was wrong. As a consequence Galileo was put before the inquisition the following year and was forced to renounce his discoveries. Galileo was sentenced to life in house arrest. However, he continued his scientific work while being in house arrest and became convinced that experiments examining several possible theories could provide clues to which theory is the best one. He also claimed that if one theory seemed compatible with observations a consequence must be that incompatible contradicting theories are be wrong. Galileo presented these ideas 1638 in the book Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche, intorno a due Nuove Scienze (Discussions and mathematical demonstrations on two new sciences). This book was later praised by both Isaac Newton and Einstein and Galileo is often called the father of modern physics.

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) from France began to study law but abandoned this topic after a while because he wanted to discover the great truths of the world. He moved to the Netherlands where he met the German philosopher Isaac Beeckmann. Beeckmann got Descartes interested in both mathematics and physics. Descartes thought a lot about how mathematics and physics could be combined. He came up with the conclusion that the universe appears to be following the laws of mathematics. Hence, mathematics should be the route to understand the universe. He wrote the manuscript to a book called World (Le Monde) supporting Copernicus helicocentric worldview. Descartes planned to publish it in 1633 postponed this when he heard about the Catholic Church’s treatment of Galileo. Iit was published in part in 1664 and the entire book in 1677. In this book Dscartes presents three laws of motion: 1) An object continues moving in the same direction unless something collides with it. 2) If a moving object pushes another object, the first object will reduce it’s motion equally as much as the other object gains in motion. 3) When an object moves every little part of the object tries to move along a straight line. Based on these laws of motion, Descartes speculates on how a universe in chaos spontaneously should collect matter in circular motions putting planets in a circular track around the sun. Another, and perhaps the most important contribution of Descartes, was the book Discourse de la methode published in 1637. In the book he states four basic rules for sound science:

- Accept as a truth only that which you yourself can understand that is true. Prejudice has no place.

- If possible, divide the problem you want to study in as many smaller sub-problems as possible.

- Start studying and finding the answer to the smallest and simplest sub-problem first. Take the most complex sub-problem last.

- Compile the results in detail not omitting any details.

The book also describes the first draft of a coordinate system which lays the foundations for analytic geometry. Many believe that the most important contribution of Descartes was the first four fundamental rule of good science. These rules with it’s fundamental skepticism towards prejudice has had a monumental impact on scientific research.

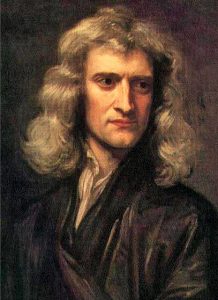

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was interested in mathematics, optics and astronomy. He was very impressed by Galileo’s works. In 1687 Newton published the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica “(mathematical principles of the Natural science’s), often abbreviated to Principia. The book presents ides about light composition, laws of gravity, how to calculate the planetary mass and how tides are explained. This book was the highlight of the scientific revolution and quickly made Newton one of his era’s most famous scientists. Although already Galileo engaged in testing theories against observations Newton took this a step further. He systematized the use of experiments to confirm theories. Furthermore, he more clearly connected mathematics and physics. The idea to solve new problems by studying the ancient philosophers was now definitely dead and Newton’s ideas came to characterize modern physics in more than 200 years.

The new biology

The ancient perception that illness was caused by an imbalance between the four humours of blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile was still prevailing in the 1600’s contemporary medicine. It was believed that blood was made, distributed by blood vessels and used up in the body. It was unknown that the blood circulated. Hence, it was considered that unused blood could stagnate in the arms and legs causing diseases. Consequently venesectio to drain “unused” blood was a common and popular method of treatment.

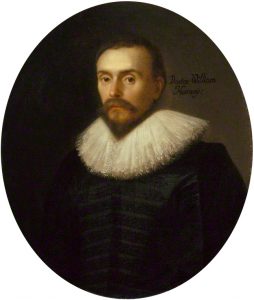

René Descartes described in 1640 some previously unpublished ideas about how the body works. One of these ideas was that blood vessels were tubes transporting blood. William Harvey (1578-1657), an English physician was, after thorough observations, in 1616 able to show that blood circulates around in the body. He lacked technical equipment to detect capillaries so he could only speculate on how the blood was transferred from arteries to veins. Despite Harvey’s discoveries bloodletting remained as a common treatment for centuries. However, Harvey’s discoveries inspired other researchers to question contemporary perceptions.

Zacharias Janssen (1580-1638), a German eye-wear manufacturer, constructed the first microscope around 1590 . Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), a German merchant saw in 1648 for the first time a simple microscope magnifying three times. He became very interested and bought one for his own use. In time he improved microscope technology, and it is believed that the best of his microscopes could magnify up to 500 times. He was the first to observed one cellular microorganisms. He did microscopic studies of muscle cells, bacteria and blood capillaries. Antony van Leeuwenhoek had no academic training at all. Although he was an amateur scientist, his observations and conclusions were of high quality and he is regarded as the founder of microbiology. With microbiology a new world of possibilities opens up.

The struggle between empiricism and rationalism during the 1600’s and 1700’s

Rationalism had strong representatives on the European continent in Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz while England at the same time had strong representatives for empiricism in Francis Bacon, John Locke, George Berkley and David Hume.

Representatives for rationalism

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) contributed to the development of mathematical and theoretical physics (see above). He presented the foundations for good science (see above). In his book Discurse de la méthode published in 1637 he discusses if there is any knowledge one can know for sure is true. He concludes a single principle, the existence of thoughts. He says that he is a thinking being and formulated this in the famous phrase; I think, therefore I am. Descartes asks if there is anything else you can be sure of. He uses the example of a figure made of vax. His senses gives him a picture of its shape, color and texture. However, it will rapidly change both shape, color and texture if it comes near any kind of heat source. Subsequently all sensory impressions of the figure will change despite its nature, a piece of wax, remains the same. Descartes concludes that our minds are insecure and to understand the true nature of things, we can not rely on our senses but only on our mind. Descartes rejects the observation of reality as a method to reach new knowledge and argues that the only way is to philosophically examine new ideas and thus devise new truths (called deduction).

Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677) worked as a young man in the family trading company. Later he left the company and devoted himself entirely to philosophy. Much of his thinking is focused around the right to think freely. However, the times were not ready for these views and he was subsequently persecuted. Due to his religious views he became expelled from the Jewish congregation in Amsterdam and shortly thereafter he was subjected to an assassination attempt. From a philosophical point of view he saw mathematics as the ideal form of science. He was a pure rationalist believing that any observation or sensory input had no value in the process of producing new truths.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) grew up in Leipzig, Germany. His father, who was professor of philosophy, died when he was six years old. Gottfried began reading his father’s books and at age 12, he had learned Latin and partly Greek solely by himself. At the age of 14, he began studying at the University of Leipzig. At the age of 20, he finished with degrees in law and philosophy. The same year he published his first book, his dissertation in philosophy. Leibniz was involved in many scientific issues and he invented differential calculus around the same time as Newton. It then became a battle between them as to who was first. Leibniz thought that many different sciences, and even human conflicts, could be reduced to mathematical or strictly logical problems.

Representatives for empiricism

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) stressed the importance of eliminating subjectivity in research by using a methodical and systematic approach. In this respect, one can say that he was one of the first philosophers of science. Bacon advocated unprejudiced study of the reality and, making conclusions and formulate new theories based on these observations (called induction). Bacon believed that by using a proper empirical method anyone would be able to do research and he predicted that this would quickly lead to major changes in society. History showed that it was not quite as simple as Bacon thought. Although Bacon’s inductive empirical method is not applied today in the same way as Bacon himself used it, his thinking about methodological approaches remains valid and he is regarded as one of the fathers of positivism (positivism is explained further down). John Locke and George Berkeley continued to drive Bacon’s idea that knowledge can only come from sensory impressions (observations). Bacon, Locke, and Berkley stated that studying reality is the best pathway to acquire true knowledge of an objective reality.

David Hume (1711-1776) was essentially an empiricist and dismissed rationalism as a logic that was not about reality. The starting point for any certain knowledge, according to Hume can only be observation of the reality. Hume is usually considered as an empiricists but he realized after a while that even empiricism was not without problems. Hume noted that empiricism used observations to induct general theories. Hume was also able to show that the idea that observations by induction could lead to a new theories may not always be correct.

This is called Hume’s paradox and can be exemplified by the following. Suppose I observe 100 swans and all are white. I see no black swans at all. Empiricism leads me to conclude that there are only white swans. The basis for doing this empirical conclusion is based on the idea of empiricism and induction has worked in the past and therefore I assume that it will work even now and in the future. Hume was able to show that this will inevitably end up in a circular argument; Induction works now and in the future as induction has worked in the past. What if the 101st swan is black? The consequence of Hume’s thinking was that although empiricism seems to be the best choice it also rest on a somewhat loose ground.

The dilemma is partly resolved

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) grew up in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). At the age of 16, he began studying at the university. He studied philosophy, including Leibniz and other rationalists. He also took great impression of Hume’s thoughts and realized that the problem Hume presented was serious. He published in 1781, after eleven years of intense deliberation, the book Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason). The book, which is now considered one of the most important philosophical writings, was 800 pages long, written in German and very difficult to read. In his book Kant tried to combine the best of rationalism and empiricism and gave science a firm basis through a model for philosophy of science where one of the main ideas was that reality as we perceive it is partly a product of ourselves. Maybe there is an objective reality but we cannot know much about that. What we are experiencing is a processed product. It follows that what we study in our science is the perceived reality, not a hypothetical objective reality that exists independent of any observer. We can experience the phenomenon but not things in themselves. Kant’s ideas is the first embryo of what later developed into the human sciences (see below).

The emergence of positivism

The term positivism was introduced by Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825), a Frenchman who, in addition to laying the foundations of French socialism, also stressed the superiority of empiricism. The faith in empiricism ability to create the ideal utopian society evolved almost into a religion. It was felt that mankind can create a heaven on earth by using science.

The French university teacher Auguste Comte (1798-1857) in Paris concluded that the foundation of all science is mathematics. He stated that man can gain true knowledge and build paradise on earth using science with a strong emphasis on mathematics. Comte embraced Sain Simon’s thoughts about positivism and was the first to consistently and systematically apply these principles to everything.

Positivism in Comte’s version had some religious traits. They had public meetings where positivism was preached, and they had their own hymn book. The positive belief in science was turned an ideal for all science, positivism, claiming that true science… (from Mårtensson & Nilstun 1988)

- is entirely based on the raw data in the form of observations.

- produce knowledge on cause and effect.

- is objective and presupposes freedom from preconceptions.

- is the opposite of non verifiable speculation.

- prefer quantitative methods and specially mathematics rather than qualitative methods.

- has its value in its technical and social applications.

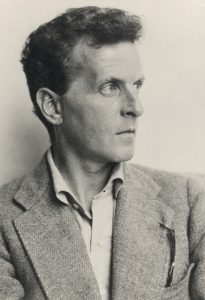

Ernst Mach (1838-1916) was a famous Austrian positivist. His ideas about positivism was considered important by many, including Albert Einstein (1879-1955) and Moritz Schlick (1882-1936). Moritz Schlick was born in Berlin. He studied physics at the Universities of Heidelberg, Lausanne and Berlin. One of his tutors was Max Planck. Moritz received his doctorate in 1904 with a thesis on the refraction of light. Soon, he began to ponder questions about the nature of knowledge and published several books on the subject. After some short-service in Rostock and Kiel, he became professor in Physics in Vienna in 1922 . In Vienna there was previously regular discussions about science and philosophy between 1907-1912. When Schlick came to Vienna in 1922 he reinstated these meetings with regular discussions around the philosophy of science. The group in Vienna took great impression of Ludwig Wittgenstein‘s book Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus published 1918. In 1928 they founded the Ernst Mach Society and in 1929 they published the first results of its discussions; The Scientific Conception of the World. The Vienna Circle. They were then nicknamed the Vienna Circle. Their reasoning was essentially that the only thing we can know something about is what we can observe. Their philosophical orientation was named logical empiricism or logical positivism. Their main requirements for acknowledge a knowledge as scientific was that it could be verified. Hence, good scientific quality according to logical positivism was characterised by (Martensson & Nilstun 1988):

- Only the reality that can be observed is studied.

- Theories that can’t be verified verified is considered meaningless. (This is called the verification principle).

- Metaphysics can not be verified and is therefore meaningless.

- Scientific theory is a system of universal laws.

- A theory has a theoretical language and an observation language.

- A theory can be confirmed by predictions being fulfilled.

- If there are several competing theories the most likely one should be selected.

- Scientific knowledge grows with time.

The Vienna Circle was dissolved when the Nazis came to power and many of its members emigrated to the United States. Moritz Schlick was killed in 1936 by a Nazi sympathizer.

Many logical positivists saw as their task to reform the “less developed” sciences to work after the principles of positivism. The logical positivism wanted to push the basic ideas in positivism to be the unifying factor in all forms of empirical science. Hence, in their view positivism was the only true scientific method applicable to all situations. The scientific achievements during the past 100-200 years are so great that few question the value of a positivistic approach in empirical physics, bio-medical science and similar forms of science studying phenomenon guided by the known laws of nature.

However, logical positivists also perceived positivism to be the only scientific method also in sociological research, that is, in areas outside the natural sciences where simple laws of nature is not enough to explain what happens. This idea is controversial and a source of heavy criticism of positivism. The epistemological criticism of positivism does not apply when positivism applied to empirical science studying phenomenon guided by known laws of nature. The criticism focus on the situation where positivism is applied to study opinions, perceptions, experiences, etc. An example is if opinions are better studied using questionnaires with fixed response alternatives analysed with statistical methods (positivism) or if these phenomenon are better suited to be studied with deep interviews and analysed with qualitative methods (more about this further down).

Post positivism

A reaction against the orthodox positivists claim to have invented a scientific approach suitable to all problems began with that Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) described a more pragmatic approach called pragmatism. William James (1842-1910) went further and suggested that the reality is a complex mosaic of experiences that can only be understood by using several approaches. The term radical empiricism was described meaning that any attempt to describe the reality only on the physical level omitting aspects such as value and meaning will fail to provide a true description.

John Dewey (1859-1952) argues the same thing as Saunders Peirce and James, but instead uses the term immediate empiricism. Post positivism gradually emerges from these ideas. Post-positivism differs from positivism by arguing two things; firstly, that the observer and the observed can not be completely separated. As a result of this they argue secondly, that there is no common shared reality. Although the representatives of post-positivism not quite imagined what we today label as contemporary human sciences (human sciences described below), one can see that some ideas in post-positivism resemble the human science concept of a the life-world perspective (see Are phenomenology and post positivism strange bedfellows?). Important representatives of post-positivism are Karl Popper (see below), Nicholas Rescher (1928-) and Thomas Kuhn (1922-1966).

Karl Popper and critical rationalism

The philosopher Karl Popper (1902-1994), born in Austria by parents of Jewish origin. He was first active as a teacher in Germany, where he also received his doctorate in psychology in 1928. Having Jewish parents the threat of Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria made him move in 1937 to New Zealand where he became lecturer in philosophy. In 1946 he moved to the UK. He remained active as a philosopher until a few weeks before his death.

According to positivism observations should lead to conclusions in the form of theories about what is true. This process is called induction. Positivists argue that each new observation that match the hypothesis verifies (confirms) it. However, Popper was very critical towards this and argued that even though never as many observations, we can never be sure that a hypothesis is 100% true.

Popper stated that we instead should try to show that existing theories or hypothesis are false. He said that our research should be focused on trying to falsify our own hypotheses. We can say that our hypothesis is a provisional truth if we fail to prove it being false. Provisional means that the hypothesis may be falsified and consequently rejected in the future. Popper argues that what separates scientific theories from non-scientific (metaphysical) theories is the possibility to falsify it. This means that you must be able to articulate what must not happen if the theory / hypothesis is true. This approach is often labelled “empirical falsification”, where you first set up a hypothesis / theory, which you then try to disprove. The work will then go on to see if you can observe an event that should not happen if the theory was true. Popper published his ideas for the first time in 1934 in the book Logik der Forschung (The Logic of Scientific Discovery). In modern statistics we often calculate a p-value. The p-value states the probability of getting the observed data given that the null hypothesis is true. This part of statistics tries to falsify the null hypothesis and this idea comes from the philosopher Karl Popper.

As mentioned above, the English philosopher David Hume stated that induction (the method empiricists use) was not entirely reliable. Hume stated that although the sun raise above the horizon every morning for as long as anyone can remember, this can not be taken as evidence that the sun is guaranteed to raise the next morning too. Popper responds to Hume’s criticism of empiricism by admitting that we do not know for sure. Although we can’t know for sure that the sun rises every morning, we can make assumptions (hypotheses). The assumption that the sun rises every morning is a hypothesis. When it actually makes it the next morning, we conclude that we have not yet managed to falsify the hypothesis that the sun rises each morning. This hypothesis about the rising of the sun then remains as a temporary, yet not falsified hypothesis. This is as close as we will get to the truth. Thus, Popper connects his response to Hume’s criticism of empiricism to his reasoning of falsification.

The chicken or the hen, what comes first? By tradition empiricists stated that we objectively make observations and based on these we see the truth and formulate a scientific theory. However, Popper argues that it is the other way around and it all starts with a hypothesis / theory. These hypothesis / theories can be tested by attempting to falsify them. Popper therefore rejects empiricism and believes that scientific theories are developed through thinking (deduction used by rationalists). Popper introduced the term critical rationalism as the name of the approach empirical falsification. Karl Popper is considered one of the greatest philosophers of science during the twentieth century and he was given many honours and awards in his lifetime.

There are examples of people who have applied critical rationalism even before Popper described the underlying philosophy. Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) was born in Hungary. His parents had planned that he would become a lawyer. He himself was, however, instead interested in medicine and began his studies in Budapest. He switched campus to Vienna where he received his medical degree in 1844. He was interested in obstetrics and surgery. In July 1846 he became director of the first clinic in the institution of maternity at the University Hospital in Vienna. This clinic had a mortality rate of puerperal fever of 12-13%, which was significantly higher than clinic 2 at the institution of maternity who had a mortality rate of about 2%. Clinic one even had higher mortality than in the women who chose to give birth to their children in the street. An investigation at the hospital set up several theories (hypotheses) for possible causes:

- Bad air caused illness and death. The air that reaching clinic 1 and 2 seemed to be similar so this cause was dismissed.

- High density of patients led to worse conditions causing illness and death. However, no major difference in patient density was seen between the clinics. If any difference clinic 2 was more crowded than clinic 1 so this theory could be dismissed.

- Clinic 1 were teaching clinic for medical students while clinic 2 taught midwives. It could be that medical candidates were unskillful and injured women to a greater extent compared to midwives. No difference in physical lacerations were seen between clinics so this theory was dismissed.

- The mortality among women was psychosomatic caused by the priest walking to visit recently dead people and the sight of him frightened women. Semmelweis persuaded the priest to go another route avoiding clinic 1, but this did not affect mortality.

The reason for the high mortality remained a mystery but in 1847 came an unexpected breakthrough. His colleague Jacob Kolletschka fell ill after accidentally injuring himself with the knife during an autopsy. Jacob died and Semmelweis noted that his symptoms and disease progression was similar to the illness affecting women at the maternity clinic. Semmelweis hypothesized that dead bodies contain a substance which could be transferred to patients and make them sick. At this time no one knew anything about bacteria or viruses so Semmelweis thoughts in the first place was a kind of poison. Semmelweis ordered that all physicians and medical students who have been on an autopsy must wash their hands in chlorinated lime solution before they could go into the maternity ward. After instigating this simple routine mortality among women in clinic 1 immediately dropped to about the same level as at the clinic 2. Semmelweis even tried to wash all the instruments used in the maternity clinic before being used again. Through this, he could almost wipe out puerperal fever.

Semmelweis’s director, Professor Johan Klein, was away at the time of Semmelweis experiments. He was not happy about the development when he came back and averted the routine of washing hands. Johan Klein was the one who had arranged for medical students to do autopsies and simultaneously learn obstetrics at clinic 1. Admitting that Semmelweis was right would have meant a recognition that the study scheme for medical students as Johan Klein set up was taking the lives of a lot of women. Semmelweis was fired in 1848 and forced, probably for economic reasons, to return to Budapest. The mortality rate from puerperal fever increased again at the maternity clinic 1 in Vienna, and was approximately 35% as late as 1860.

Semmelweis introduced his routines for hand washing and washing of instruments in Budapest and reduced mortality from puerperal fever to 0.85%. Semmelweis ideas became popular in Hungary, but the rest of Europe did not embraced his ideas. One of Semmelweis weaknesses, that probably reduced the dissemination of his ideas, was his uninterest or inability to scientifically describe his findings and publish them. Finally, in 1861 he published the book Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers (The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever). The book was given harsh critique making Semmelweis upset and in affect writing several open letters to different professors. At this time the connection between microbes and disease was not discovered so Semmelweis’s ideas was dismissed in most of the medical establishment. As a curiosity can be mentioned that the term “Semmelweis reflex” means to automatically dismiss “unsuitable” new information without closer examination. Although Semmelweis did not add any new theoretical concepts within philosophy of science his work is considered to be a good example of critical rationalism.

After several years of increasing mental ill health Semmelweis had a nervous breakdown in July 1865 . Possibly he had Alzheimer’s disease (a form of early senile dementia). He was taken to a mental hospital where he died after 14 days. According to tradition, he died of a wound infection but according to recent information it is believed his death was due to physical violence from the institutional staff, perhaps causing a wound. Semmelweis died at the age of 47.

Overview of philosophy

Terms common in philosophy has been mentioned above and before we continue, it may be appropriate to give a brief description of some of these. The word philosophy may have been introduced by Pythagoras (570-497 BC) and is derived from the Greek Φιλοσοφία (Philosophia). The word consists of the roots philos = love and sophia = wisdom, and can be translated as love of wisdom. Let’s start by describing the most important branches of Western philosophy. There are of course several different ways to give a brief overview of philosophy and the one below is not the only one.

Theoretical philosophy

Theoretical philosophy deals with overarching principles. The most common subgroups are:

- Metaphysics ≈ Natural philosophy

- Epistemology

- Logic

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Consciousness

- Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Science

- History of Philosophy

Metaphysics, epistemology and logic are usually considered being the main branches of theoretical philosophy. The other branches of theoretical philosophy consists of ideas taken from these main branches.

Metaphysics ≈ Natural philosophy

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that deals with questions around the fundamental nature of reality and seek to make rational statements about fundamental assumptions about the existence (Ontos), our world view. Metaphysics can also discuss things we can not perceive with our senses, which are beyond the physical. Issues addressed is how nature is constituted ?, Is God ?, What is man’s place in the universe? and concepts of existence, space, time and causality.

One of the main branches of metaphysics is ontology. It is the study of the concepts or categories you need to adopt in order to provide a description and explanation of (some part of) reality. Simply put, the ontology describes different worldviews. Examples of polar opposites (different world views) are:

| Realism / materialism ↔ idealism: | Realism / materialism states that the external, material reality exists independently of human consciousness.

Idealism, however believes that the only thing that can exist independently of everything else are spiritual or moral phenomena. The material physical world is either in the deepest sense also spiritual, or alternatively can only exist as an objects of consciousness. The epistemological construct of this duality is atomism versus holism (described previously). |

| Existentialism ↔ dialectic: | Existentialists states that the existence of experience can never be the object of objective knowledge. “Subjectivity is the truth”: It is only in actual existence, through the way of living and acting, not by pure contemplation, that man can reach a truth that is good enough to live and die on. We choose – intentionally or unintentionally – our way of life. Our freedom provides an absolute responsibility and inevitably leads to anxiety.

In contrast dialectics states that we can reach the highest knowledge through logical reasoning. Plato saw dialectics as the highest science. In dialectics you were liberated completely from the senses and followed purely logical reasoning. The epistemological construct of this tension is the duality empiricism versus rationalism (described previously). |

Epistemology

Epistemology asks questions like: What is knowledge? What can we have knowledge about, an objective external world or just our own experiences? What is the ultimate basis of our knowledge, the senses or the mind? How is new knowledge produced? Has anyone (priests, women, scientists) precedence over others in seeking new knowledge?

Important concepts in epistemology are structuralism (individual elements can not be analyzed in isolation, searching invariance behind variances), constructivism (knowledge and perception of reality is not objectively existing, but structures made of subjects) and relativism (there are no absolute truths). As for ways to create new knowledge, you end up in the two opposites:

atomism ↔ holism

empiricism ↔ rationality

(These opposites are previously described)

Logic

The origin of Logic is considered to be Aristotle first systematization of correct and incorrect conclusions. Modern logic is an abstract science which lies on the boundary between philosophy and mathematics which also has ties to computer science, linguistics and cognitive science.

Other branches of theoretical philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

Philosophy of language asks questions about the nature of language: What does it mean that a word has a meaning? How does the language relate to our consciousness and reality? Although philosophers talked about language ever since Plato’s days philosophy of language were not a specific branch within philosophy until the 1800s. - Philosophy of Consciousness

One of the big questions in philosophy is about the relationship between the mind and the brain. According to monism consciousness is directly linked to and a function of the brain’s complex electrical and biochemical processes. A contrary view, dualism, says that consciousness is beyond the physical world and is independent from this. - Philosophy of Mathematics

Philosophy of Mathematics asks basic questions like: What is mathematics and how should it be used. - Philosophy of Science

Philosophy of science deals with scientific knowledge and originated primarily in the fields of philosophical metaphysics and epistemology. When the philosophy of science goes down on a more practical level and form theories about how scientists use their theories (science about science) we call this theory of science. With the concept theory of science we mean knowledge and research about research. This web-page is about philosophy of science and theory of science. - History of Philosophy

History of Philosophy explains both how various problems and issues in philosophy previously appeared and how they were answered through history. The history of philosophy describes this process and may provide suggestions for solving future philosophical problems.

Applied philosophy = Practical philosophy ≈ Philosophy of values

Applied philosophy influences our daily lives more directly than theoretical philosophy. The most important branches of applied philosophy are:

- Ethics

Ethics studies the moral concepts of good and justice, and if these concepts are universal or dependent on various factors. Key questions are “what’s good”, “what is right”, “how one should behave”. - Aesthetics

Aesthetic issues, especially poetry, were lively discussed in ancient Greece. Aesthetics as an independent philosophical science was introduced in 1735 by Baumgarten in a thesis on poetry. - Philosophy of Religion

Philosophy of Religion consists of the classical philosophical areas metaphysics, epistemology and ethics. Examples of questions dealt with are: Is there a God, and if so how is the nature of God? Can you prove or disprove the existence of a God? What conclusions can we draw from people’s religiosity, whatever that is? Do you have to provide reasons for a religious belief? How does science relate to religion? What is the relationship between religion and morality? Is God’s goodness consistent with the apparent evil in the world? - Philosophy of Law

Basic questions in philosophy of law is “What is the law?”, “Is power the same as having a just cause?” and “what is the difference between law and morality?” - Philosophy of Politics

Philosophy of politics focus on phenomena in societies, different ideologies and theories of society’s structure and function.

Emergence of the human sciences

Positivism was the scientific ideal since the early 1800s and had a very strong position. Positivism had a clear method of how new knowledge could be developed. It aspired to become a universal scientific approach applicable to all forms of research. Some philosophers stated that the idea of a universal scientific approach applicable to everything was a logical error. The other opposing scientific ideal, which began to emerge from the late 1800s and onward, was human sciences.

Systematic hermeneutics

Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) considered it difficult to use positivism in the interpretation of literature. Instead, he took the basic ideas of interpreting the Bible and other classical texts and made a structured scientific method for the interpretation of any oral or written statement. The structured method he developed is labelled systematic hermeneutics. Schleiermacher was of the opinion that:

- Anyone who interprets a statement must have knowledge of the author and the context of the author.

- The goal is to obtain the original thought of the author.

- Misunderstanding is the natural state. The truth (= the author’s original idea causing him to write the text) can be obtained by using a structured approach to interpretation.

It is according to Schleiermacher possible to grasp the author’s original idea by studying the statement together with the author and the context / culture in which the author lived. A good researcher can find the only true interpretation and different researchers should, according to Schleiermacher, arrive at the same result. Hence, Schleiermacher has a positivistic trait in that he believes it is possible to find the true meaning of a statement / text. This is not true positivism but can be considered as an element of positivist thinking. Contemporary literary scholars sometimes use Schleiermacher’s method today.

Positivism versus human science

Immanuel Kant was both an empiricist and rationalist. He also presented a foundation for human sciences by introducing the idea that objective reality (if it exists) is not directly accessible to us. We only have access to the reality filtered through our senses. Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911), who was professor of philosophy in Berlin, was influenced partly by Immanuel Kant, but also by Schleiermacher’s ideas on interpreting texts. Dilthey saw how some kind of interpretation of observations could be an opening to understand things that was hard to understand using a purely positivistic approach. He voiced the idea that research on people’s cultural and social life works according to other principles and are not accessible using the positivistic approach. The idea of a universal scientific approach applicable to all forms of research seems faulty. Dilthey coins the statement “We explain nature but understand spiritual life.” Dilthey gave the modern human science legitimacy.

A Life world perspective

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) was a German mathematician. He received his doctorate in 1882 for a thesis on calculus of variations. He first interest was mathematics and the philosophical foundation of mathematics. However, he gradually changed his views, left mathematics and went on to focus on philosophy. Around the early 1900 he began to criticize contemporary scientists for moving away from something he called the life-world. He stated, as Immanuel Kant previously did, that we can not catch a true description of the real phenomenon, only the human experience of it. The human experience transforms the real phenomenon to a subjective phenomenon. Humans act upon what they see and understand, not how it is. We can not describe a phenomenon objectively but only the human experience of it in the form of a phenomenon.

The life-world theory launched by Husserl permeates not only phenomenology but also life world hermeneutics and more or less all qualitative research. The theory implies that we can’t catch a description of the truly “objective” phenomenon, only human subjective experience of it. Life-world is the world as we perceive it. The life-world consists of memories, our everyday world (= the experience of the everyday life without any reflexion) as well as future expectations. It was Husserl’s firm opinion that scientific research around people’s perceptions must be based on the “life-world” concept because that is the world in which we perceive we live in.

Phenomenology

Husserl introduced phenomenology which quickly became known by the slogan “to the things themselves.” Phenomenology is the study of phenomena as they are experienced. Phenomenology is a theory of the subconscious. Husserl’s main contribution to the knowledge of philosophy was to say that man experiences the world through experiencing a phenomenon. To know anything, we have to go to the phenomenon (phenomenon = whatever we are interested in as it turns out).

Husserl believed that the researcher can and should put their own existence (= preconceptions = prejudices) aside to find the true essence of a phenomenon. Hence, empirical studies with phenomenological approach seeks to avoid interpretations. An important element of avoiding subjective interpretations is that the researchers hold back their own understanding so that the true phenomenon can appear. One major criticism towards phenomenology is that perhaps it is not in human power to completely put their own preconceptions aside. The consequence of this criticism is that it may be impossible to completely avoid interpretation.

(1908-1961)

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) says that, in order to capture the phenomenon we must go beyond the prejudice of an objective world to instead consider a subjective lived world in which the body plays a central role. He stresses the indivisibility of man, that is, we do not have a body but we are our body. The body can not be seen as a separate object. An example of a study based on Merleau-Ponty’s theories was performed by a high school nurse faced with high rates of smoking among students:

This web page describes the most important cornerstones of Western philosophy of science. It is not complete and, if necessary, will be supplemented and revised. Philosophy of science is based on the parts of philosophy that asks questions about the nature of scientific knowledge. How do we know what scientific knowledge is and how does it differ from any kind of knowledge? Which pathways are acceptable and trustworthy when you create new scientific knowledge? This web page begins by describing the development of scientific thinking until post positivism after which a very brief overview of philosophy is given. The web page continues with a brief description of how human science has developed. Many names of people are mentioned (and more names should perhaps be mentioned) but there’s no need to learn all the names by heart. Towards the end, a proposal for what may be worth remembering is given.von Bothmer, Margareta. Rudebeck, Carl-Edvard. Understanding the meaning of smoking behaviour through the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty. Theoria : journal of nursing theory, ISSN 1400-8033, Vol. 12, no 2, 5-12 p

Abstract [en]: The aim of the study was to explore the meaning of smoking behaviour by applying the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty. Behaviour is a result of body-mind reacting on its world and is always intentional. The meaning of smoking behaviour is discussed in relation to body and space, formation of body image and identity, and learning of a habit. A habit is entrenched at the bodily level and in order to change the habit, the person has to re-identify herself at the bodily level as well as at the cognitive and emotional levels. It is suggested that the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty could be used in practice and research to improve smoking prevention and cessation strategies.

This study is a good example of rationalistic-holistic research (lower right quadrant on the epistemological world map).

Husserl was a philosopher who basically did not leave the desk. Hence we can label Husserl as a rationalistic-holistic researchers (residing in the lower right quadrant of the epistemological world map). Amadeo Giorgi, an American psychologist, was one of the first who started to empirically apply phenomenology through data collection and analysis of data collected. As Giorgi transferred phenomenology from being solely a rationalist-holistic science philosophy to also become an empirical-holistic scientific approach. Giorgi published in 1970 the book Psychology as a Human Science. In the book, he argues that psychology is more about human science than science using a positivistic approach. It is very important during the data acquisition and analysis to follow a very strict methodology in Giorgi’s model of phenomenology to be able to describe the true essence of the phenomenon. The idea that the true “objective” essence can be identified if you follow a rigorous method has by some been considered as a trait of positivistic thinking. Despite this Giorgi’s approach would definitely be placed under the empirical-holistic paradigm (the upper right quadrant).

Life world hermeneutics

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) published in 1927 the book Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), by many regarded as one of the most important philosophical works in that century. He asks the question what does it mean to be. Heidegger has been described as a philosopher of “being there”. Heidegger adopts Husserl’s notion of the life-world (we can not describe a phenomenon objectively but only the human experience of the phenomenon). Unlike Husserl, Heidegger does not think that we can put our prior understanding of a phenomenon in parentheses. For Heidegger’s it is clear that we are always standing on the foundations of our preconceptions when we interpret observations. The interpretation is in focus in Heideggers approach.

Schleiermacher ‘s hermeneutic approach aimed to understand the author. However, Heideggers hermeneutic approach partly aims to understand the preconception of the reader of the text. For Heidegger, one of the main preconceptions for humans is the knowledge of your own mortality.

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) was in the 1920s one of Heideggers students and was very influenced by him. Gadamer further develops Heidegger’s thinking that preconceptions can’t be put within parentheses. Gadamer spent many years of his life figuring out how to formulate his thoughts and finally in 1960 he publishes the book Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutics (Truth and Method). He unites Husserl’s life-world perspective and Heidegger’s philosophy of existence to a philosophy of the basic conditions of human understanding which form the basis of his hermeneutical approach.

In the book, Gadamer argues that the relationship between truth and method is complicated. He criticizes Schleiermacher’s methodological hermeneutic approach aimed to achieve an objective truth. He argues that we can hardly claim to know the objective reality, but we can interpret it using our own preconceptions. His hermeneutic approach is, however, open to other interpretations questioning one’s own preconceptions.

Gadamer states that my understanding of someone else is always based in my own preconceptions. He also believes that rigorous scientific methodology prevents one from understanding. One should not master the text but rather try to become its servants, lose yourself in the text or the spectacle. If the researchers is not surprised by anything in the own result it probably indicates that the researcher’s own preconception probably had an excessive influence over the analysis. Gadamer’s conclusion is that we should try to make us aware of our own preconceptions and there is no given ideal scientific method, just try to be open. A life-world perspective requires openness.

A new experiencing is according to Gadamer an event and also an encounter. A new experience is to discover how something is, but also how something is not, that is, to see that something is not as it was assumed to be. When you see something in a new light this experience changes yourself and makes you grow. Growing and re-configuring your preconceptions can sometimes be a painful but necessary process for those who really want to acquire new knowledge.

Preconception and interpretation are intertwined and understanding can’t be achieved without preconception. So where does our preconception come from? Gadamer answers: from the tradition that we are living in! Traditions influence our perceptions, both of the present and of the tradition. Preconceptions can be a barrier to openness. It can be a “bias” or “prejudice,” or something else that should not be taken for granted, but is something that can be changed.

Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) began to study philosophy in the Sorbonne in France 1934. He was drafted into the French army in 1939 and in 1940 he was imprisoned by the German puppet regime in France. He spend the rest of the war sitting in a German prison camp where he met with several other intellectuals who probably influenced him. After the war he became a professor in Strasbourg 1948-1956. 1956-1965 he was professor at the Sorbonne University. 1965-1970 he worked on a new University (Nanterre) in the suburbs of Paris where they experimented with new novel teaching methods. After unrest at the university in 1970, he moved to Chicago where he worked as a professor. In 1985 he returned to Paris and was at that time relatively unknown in Europe.

Ricour consider the text, not the author, to be the main focus. The text hides more things than the author had in mind. The main focus is what you get out of the text, not the author’s intentions with the text. Hence, the focus of the interpretative act is not the author’s intention with the text but rather what you see in the text. Ricour also introduces elucidation into hermeneutics. Human actions can be regarded as analogues to texts.

A contemporary hermeneutic approach argues that interpretation and understanding are cornerstones of what we call humanity (Dahlberg, Drew & Nyström 2001). However, hermeneutics is not entirely uniform, various versions exists. In summary, hermeneutics would answer the question: “What is it that becomes visible and what is the meaning of it?”. The most important philosophers contribution to life world hermeneutics can be summarized as:

| Philosopher | “Contribution” |

|---|---|

| Dilthey (1833-1911) | We can explain nature but we can’t explain the human nature, only understand it. Dilthey also lays the base for the life world perspective. |

| Husserl (1959-1938) | He states that humans act upon what they understand, not how it really is. Husserl defines the life world perspective. He states that the true essence of a life world phenomenon can be found and this is more important than the findings produced within positivistic science. |

| Heidegger (1889-1976) | He accepts Husserl’s life world perspective but adds on that humans are always interpreting. The consequence is that we can never state that we have found the truth, simply a truth. There is no single true description of the life world. |

| Gadamer (1900-2002) | The positivistic influence has formed parts of human sciences too much. The truth is never grasped by a specific research method. Sincere openness can bring us closer to the truth but not all the way. There is no true interpretation, only alternative more or less fruitful interpretations. Gadamer does not give us a detailed scientific method, he prefers to talk about scientific approaches. Gadamer is often perceived as the most important philosopher for modern hermeneutics. |

| Ricour (1913-2005) | Hermeneutics as a scientific approach is not simply about understanding, it also has important components of reflextion and interpretation. Ricour emphasizes the importance of interpretation in life world research. |

Preconceptions (=prejudices)

Our preconceptions are considered to have a great importance in empirical-holistic (qualitative) approaches such as phenomenology and life world hermeneutics. Preconceptions may have different meanings in different empirical-holistic approaches. In phenomenology preconceptions must be made aware and then overridden to avoid that they contaminate the interpretation of the data. It is different in life world hermeneutics where preconceptions should be made aware, understood and then be used as an important tool to interpret the data collected.

What are preconceptions? Hans-Georg Gadamer states that three phenomenon influences our understanding of our life world; our horizon of understanding, our culture’s historicity as well as our own personal history. These three phenomena makes up our preconceptions or prejudices and this becomes an obstacle to openness. Both Husserl and Gadamer states that it is important to try and clarify the conscious part of our own preconceptions. The unconscious part is unfortunately hidden for us. Gadamer emphasizes the importance of broadening your own horizon of understanding, clarify our culture’s historicity and to become aware of the possible influence of your own personal history.

Our horizon of understanding

Gadamer says that it is difficult to understand a phenomenon residing outside your the limits of your own culture. The limit of what we can understand is called the horizon of understanding or horizon of meaning. In some areas there are taboos and the horizon of understanding close quite near. In other areas the horizon of understanding may extend much further.

The influence of our historic-cultural context

A major cause of cultural boundaries is that people are more or less tied to their historical background. For example the contemporary Western culture is based on four historic pillars (other cultures may have different historic pillars making up their historic-cultural context):

| Historic pillar | Geographical starting point |

|---|---|

| Jewish-Christian-Muslim tradition | Jerusalem |

| Democratic ideals and values | Ancient Greece |

| Industrialization | Manchester, England |

| Digital revolution and information age | US (quickly spreading globally) |

Our own personal history

We are not only influenced by our historic-cultural context but also by the genetic predisposition laying the foundation for our personality and our own childhood with early experiences and memories. Although we often revolt during a period of our life, many of us tend over time to become like our parents.

The consequences of preconceptions

An important question in phenomenology is whether the researcher has successfully put their own preconceptions aside to allow the true essence of the observations to appear. Any reader of the final results would like the researcher to report their preconceptions so that anyone who examines the results of the study can assess if the researcher reasonably have managed to set aside their preconceptions. Aiming for this “objectivity” is important within phenomenology.

Contrary to phenomenology the life-world hermeneutic approach considers the researcher and the researchers preconceptions as an integrated part of the study, like being a part of a survey instrument. Is the method including the researchers preconceptions reliabel? The only way this can be ensured is trough complete transparency about all steps in the project, including the researchers preconceptions and how these have been allowed to influence interpretation of observations. No scientists can be totally objective according to Gadamer. If the researcher understands this and become aware of their own preconception it enables the researcher to be more open and transparent. The fact that the researcher has preconceptions requires a large proportion of self-criticism from the researcher. Gadamer further points out that another consequence of having preconceptions that we can’t override is that there is no “correct” interpretation, only alternative more or less fruitful interpretations. Hence, in life-world hermeneutics it seems more reasonable to talk about a temporary current understanding. Future deepened understanding grows slowly in a circular motion between the individual’s preconceptions and new observations and ideas, leading to new understanding, which in turn will be the new preconception in future interpretation of observations. For each turn the researcher reaches a higher level of understanding in what is called the hermeneutical spiral.

Grounded theory

In the early 1960s sociological research were characterized by to be construction of hypotheses and theories without any empirical basis. Barney Glaser, a statistician at Columbia University, was critical and called this “ground-less theory”. In the mid 1960s, Glaser working with Anselm Strauss, a researcher in qualitative methods at the University of Chicago. Together they did a project on problems around dying and published their results 1967 in the book Awareness of Dying. During this project they develop a new method to analyse their observations and published this in 1967 in the book The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Their main idea was that any new theory must be based on collected data, not on any predetermined theory.

Grounded theory originated in sociology and hence focus on what happens in relations between people. Grounded theory is an empirical-holistic approach which describes step by step how to create new hypotheses based on observations. Grounded theory mainly uses induction as its method (see below definition of induction).

Grounded theory gained in importance in areas such as public health and nursing research during the 1980s and 1990s. Grounded theory did not develop new concepts within philosophy of science like philosophers within the life -world concept did. Grounded theory is more a practical methodology less anchored in philosophy than phenomenology or life-world hermeneutics.

In 1987 Strauss published Qualitative analysis for social scientists and it became obvious that Glaser and Strauss had developed different interpretations on how to apply grounded theory. This divergence still exists. Later constructivist grounded theory developed with some similarities to life-world hermeneutics in that it states that grounded theory does not develop “objective theories” but rather that developed theories are a construct of the researchers preconceptions in interaction with informants.

Common concepts

Induction and deduction

Rationalists start with a number of assumed conditions. Based on these conditions they construct a new hypothesis or theory (without any observation of reality). This is called deduction. The new theory may be a prediction of how a part of reality will behave under certain circumstances. Problems arise if the reality does not seem to behave as expected. A pronounced rationalist can then argue that it is because we have measured wrong or that we do not yet have methods to verify the hypothesis. A good example of this is Einstein’s theories where it took several decades before his theories could be proved with experiments. An empiricist would in the same situation have rejected this new hypothesis and subsequently created a revised hypothesis. This revised hypothesis would then be tested against reality.

Many empiricists would alternate between theoretical deductions and the study of reality. Previously we mentioned that this approach is labelled critical rationalism or empirical falsification. This approach is very common if you use an empiric-atomistic approach (upper left quadrant). Other empiricists would not test a hypothesis against reality. They would rather unprejudiced approach reality to see which theories emerge from observations of reality. This latter approach is called induction. Hermeneutics, phenomenology and grounded theory are empirical-holistic research approaches that are all empirical and uses induction to generate new knowledge.

To summarize: The empirical-atomistic (positivistic) researcher usually use an empirical falsification (critical rationalism) approach to falsify the null hypothesis. The empirical-holistic (qualitative) researcher usually use an inductive approach. The extreme rationalist does not care about what we can learn from our experiences and the extreme empiricist takes no account of the value of theoretical speculation.

“As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain, and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.” (Albert Einstein)

A purely deductive conclusion is always valid if it is logical. However, the conclusion is not necessarily true just because it is logical. An inductively formulated conclusion is one true way of describing the reality. However, not necessarily the only way to describe the reality.

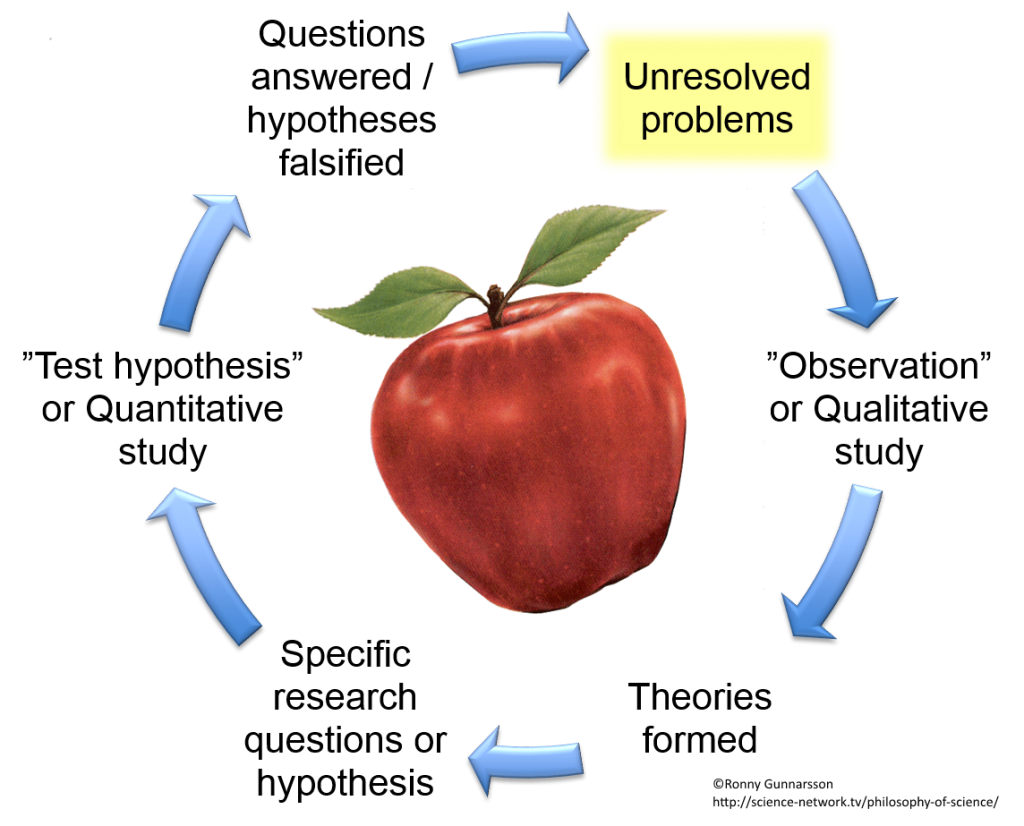

The spiral of discovery and proof

To approach reality without preconception (induction) is also known as the path of discovery, the right hand side of the figure. Taking the new theory (hypothesis) and test it against reality (empirical falsification) is the pathway of proving the theory. These two pathways are often described as two half circles that hands the process over to each other and together they form a circle. The idea is to start with an empirical-holistic approach providing a picture of how the phenomenon is perceived or described. This is the basis for the construction of one or more theories which are then tested using empirical falsification. The proving phase usually raises new questions warranting another round of qualitative research followed by a quantitative validation and so on lap after lap. Hence this version of mixed methods research becomes a spiral leading to a higher understanding for each lap.

The model of Galileo versus the model of Aristotle

As mentioned above, the two principal scientific approaches within empiricism are: